-40%

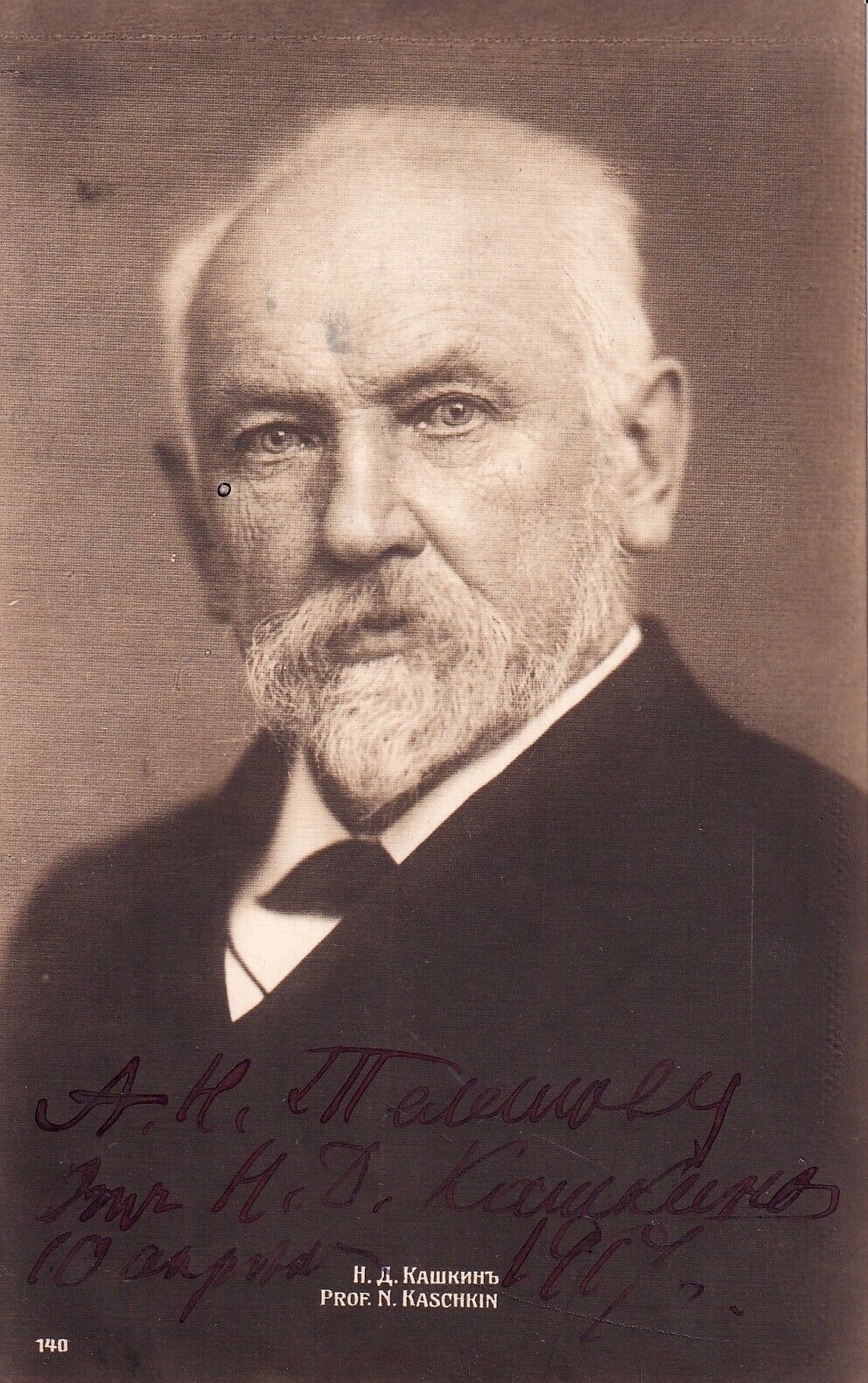

NIKOLAI KASHKIN Pianist & Tchaikovsky friend scarce autographed photograph, 1919

$ 264

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Scarce autographed postcard photograph of the pianist, critic, Moscow Conservatory Professor, close friend of Tchaikovsky and biographer of the composer to Andrei Teleshov, April 10, 1919.Kashkin (1839-1920) was born in the town of Voronezh the son of a book dealer. His father was his first music teacher. When he advanced beyond his father’s capabilities he was sent to the pianist K.K. Gepner for further lessons. After Geppner’s lessons he was self taught. By the age of thirteen he was taking in piano pupils to help pay the families bills. He also traveled as a recitalist and gained the reputation as a virtuoso and an excellent pedagogue. A polymath, he went initially to Moscow in 1860 and then intended to apply for admission to the Technological Institute in St. Petersburg, but decided he preferred to stay in Moscow as he heard the musical culture there was far superior. He was then sent by Balakriev to his old teacher Alexandre Dubuque, a Russian born John Field pupil, son of a French Marquis who had fled the French Revolution. (Field lived in Russia from 1802-1829) Dubuque taught Kashkin for free.

Kashkin through his musical friends became friendly with Piotr Jurgenson the famed music publisher. The friendship led to Kashkin living in an apartment in Jurgenson’s home. The Imperial Russian Music Society Moscow had offices in Jurgenson’s home, which regularly exposed the young pianist to Nikolai Rubinstein and other important musicians and composers including, Albrecht, Balkriev, Borodin, LaRoche and others. In 1862, the pianist told Rubinstein he intended to go to St. Petersburg to Anton Rubinstein’s new Conservatory. Nikolai talked him out of it, taught him and hired him as a piano instructor at the Moscow branch of the Imperial Russian Music Society School. In 1866 when Rubinstein opened the Moscow Conservatory, he hired Kashkin as one of the founding Professors. They even awarded him a Diploma of a Freelance Artist which usually required a test, but the other Professors unanimously awarded the diploma to him. From 1866-1893 he taught the largest class at the Conservatory, elementary theory. From 1866-1969 he taught the female compulsory piano, from 1869 to 1893 he taught the special piano class for juniors, from 1876 to 1893 he taught the history of music, from 1881 to 1893 he taught harmony for singers, from 1884 to 1893 he taught the third year solfège class and from 1885-1893 he taught harmony for singers. For a year each he taught the history of piano performance (1892–93) and the history of opera (1894–95). From 1905 to 1906 he lectured on the history of music. In addition he was a music critic for the “Russian Register” and the “Moscow Register” where he helped and hurt many a composer. Among his many pupils included, pianists Leo and Serge Conus, pianist Elena Gnesina, composer Alexandre Gretchaninov, pianist Josef Lhevinne, pianist Nikolai Medtner and his sister-in law/wife Anna and pianist Alexandre Siloti.

Kashkin today is remembered for his long friendship with Piotr Tchaikovsky. They first met in 1866. Tchaikovsky had attended the Imperial Music Society of St. Petersburg School and then enrolled in the first class of the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1862, graduating in 1865. Nikolai Rubinstein offered the young and up-and-coming composer a position as Professor of Music Theory in the inaugural class at the new Moscow Conservatory in 1866. Not part of the Moscow music scene, Tchaikovsky was ostracized by many of his colleagues there. Rubinstein organized a dinner party, where he introduced him to his closest Imperial Russian Music Society Moscow division colleagues including the cellist Konstantin Albrecht, publisher Jules Jurgenson, critic Herman LaRoche and Kashkin among the many. They all readily accepted Tchaikovsky as their colleague and friend and he gained some very important Moscow allies who were to become his initial base of support and in the case of Jurgenson, his publisher. Kashkin became useful to Tchaikovsky in several ways, as a critic he helped promote the composer throughout his life, he also named his second symphony “The Little Russian” in his review after the first performance, a name which has stuck through time. He also helped Tchaikovsky proof and edit several of his symphonies. He often invited Kashkin to rehearsals of performances of his new works for his opinions. Kashkin helped write the treatment and libretto of “Yevgeny Onegin” with him, though he does not receive credit for his work except in intellectual essays on the creation of the opera. When Tchaikovsky’s marriage quickly failed, he wrote a two page letter to Kashkin describing his despondent state and how he tried to take his own life by wading in the icy Moscow River in the hope of contracting influenza to end his life and when that failed, leaving Russia in the dead of night to escape from his obligation. Some have questioned what Kashkin was really told and whether he invented part of that story, others find it entirely plausible. When Nikolai Rubinstein was alive, Tchaikovsky and Kashkin often traveled with him and continued to do so. The Summer of 1893, Tchaikovsky lamented in several letters that his busy schedule and health had forced a cancellation of a trip he and Kashkin had planned to take hiking to the Volga River and walking up its’ banks. All of this is interesting as Kashkin was a married man and despite Tchaikovsky’s sexual orientation, he remained one of the composer’s closest friends and allies irrespective of their orientation. Kashkin accepted Tchaikovsky for who he was. Of course this is not to say that his friend irritated Tchaikovsky from time to time, there are letters written by the composer to his brother Modeste when he was angry with Kashkin and his other friends and had no one else to discuss his situation. When Tchaikovsky turned fifty, Kashkin wrote about how the composer had rapidly aged. His hair had turned white and he had developed wrinkles. During his final months the composer told his friend how young and vigorous he felt as he tackled his final work, the 6th Symphony. By the time of the premiere on October 19th, he was so fearful about the reception as the orchestra had not played the work with enthusiasm that he asked Napravnik to conduct the performance and was refused. The work was greeted with enthusiasm from the audience, but not the enthusiasm which greeted the work on November 18th, 12 days after his death when Napravnik conducted the orchestra. Kashkin and the Moscow Conservatory contingent did not arrive in time for the wake, however, they arrived in time for the funeral, where the pianist placed a large silver wreath by his friends casket. He waited for three years after Tchaikovsky’s death to publish his memoirs about the composer, Recollections of Tchaikovsky. There are a variety of opinions about the book, that said, it was well known they were close friends, letters clearly indicate that, as well as documentation in books by contemporary colleagues as well as his brother Modeste.

In 1918 with food shortages in Moscow due to the Revolution, the 79 year old professor moved to Kazan where he helped to build the conservatory system there. His text on music theory which was required in Russian music schools and conservatories was initially published through 1931 with it’s final edition.

Harmonie Autographs and Music, Inc.

Music Antiquarian and Appraiser

New York, New York

All items guaranteed authentic